Beyond the Cloud: Mastering the Shared Responsibility Model for Comprehensive Risk Management

Beyond CSPs: Why Your MSP and MSSP Must Be in Your Responsibility Matrix

Introduction: The Accountability Gap in Modern IT

The migration to cloud computing presents a central paradox for the modern enterprise. On one hand, it offers unprecedented agility, scalability, and potential cost savings, enabling businesses to innovate at a pace once unimaginable. On the other hand, this transition fundamentally alters the traditional IT ownership model, creating a landscape ripe with ambiguity and risk. When an organization moves from an on-premises data center, where it owns the entire technology stack, to a cloud environment, the clear lines of security ownership can blur, leading to a dangerous accountability gap. Misconfigured settings or weak controls on the customer side can lead to catastrophic breaches, even if the provider’s infrastructure is perfectly secure.

To navigate this new paradigm, the Shared Responsibility Model (SRM) has emerged as the foundational framework for establishing clarity, ensuring compliance, and enabling effective risk management. At its core, the SRM is a cloud security and risk framework that delineates which cybersecurity processes and responsibilities lie with a service provider and which lie with the customer. Its purpose is to reduce confusion, prevent the security gaps that arise from incorrect assumptions, and establish clear accountability for every layer of the technology stack.

However, this report will demonstrate that the traditional, two-party Shared Responsibility Model—a simple delineation between a Cloud Service Provider (CSP) and its customer—is dangerously simplistic in today’s interconnected IT ecosystem. True risk management requires a multi-layered understanding that incorporates the complex roles of Managed Service Providers (MSPs), Managed Security Service Providers (MSSPs), and the myriad of Software as a Service (SaaS) vendors that constitute the modern enterprise environment. The central thesis is that documenting these complex, multi-party relationships in a formal, detailed Shared Responsibility Matrix (SRM) is the cornerstone of modern governance, compliance, and cyber resilience. This document serves as a strategic guide for business and technology leaders to move beyond a superficial understanding of the model and operationalize it as a central pillar of their security and risk management programs.

Section 1: Deconstructing the Foundational Shared Responsibility Model

To master the complexities of a multi-vendor cloud environment, an organization must first achieve a deep and nuanced understanding of the foundational model upon which all other responsibilities are built. This involves grasping the core tenets of responsibility, analyzing how those responsibilities shift across different service models, and recognizing the common misconceptions that lead to critical security failures.

Defining the Core Tenets: Security “of” the Cloud vs. Security “in” the Cloud

The Shared Responsibility Model is universally anchored by a simple yet powerful principle articulated by major CSPs like Amazon Web Services (AWS), Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud Platform (GCP): the provider is responsible for the security of the cloud, while the customer is responsible for security in the cloud.

Security of the Cloud (Provider Responsibility): This encompasses the physical and foundational infrastructure that runs all services offered by the CSP. The provider is responsible for protecting the hardware, software, networking, and facilities that comprise the cloud itself. This includes the physical security of data centers, the integrity of the underlying compute, storage, and database hardware, and the security of the virtualization or hypervisor layer that isolates customer environments from one another.

Security in the Cloud (Customer Responsibility): This includes everything that the customer builds, deploys, or stores within the cloud environment. The customer is responsible for securing their own data, applications, operating systems, and network configurations, as well as managing identity and access. A simple but effective rule of thumb is: if a customer can configure, modify, or deploy it, they are responsible for securing it.

It is crucial to recognize that while the model’s name is “shared,” it does not imply that two parties jointly manage a single asset. Rather, the model is about a clear delineation of duties. The CSP has full and complete responsibility for the security of assets under its direct control, such as the physical server, and the customer has full and complete responsibility for assets under their control, such as their data encryption keys. The “sharing” occurs at the ecosystem level, where both parties must flawlessly execute their distinct and separate duties to ensure the holistic security of the environment. This linguistic nuance is a primary source of confusion; businesses often interpret “shared” as a collaborative partnership in security tasks, when in reality, it defines strict boundaries of independent ownership and duty.

The Shifting Lines of Responsibility: A Detailed Analysis Across Service Models

The precise line of demarcation between provider and customer responsibility is not static; it shifts dramatically depending on the cloud service model being used. As an organization moves along the spectrum from Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS) to Software as a Service (SaaS), it cedes more control and operational burden to the provider, but critically, never its ultimate accountability for its own data and access.

Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS)

In an IaaS model, the customer has the most control and, consequently, the greatest security responsibility. The CSP manages the core physical infrastructure—data centers, networking, and hypervisors—but the customer is responsible for securing nearly everything above that layer. This includes:

Guest Operating System: The customer must manage, patch, and harden the OS.

Applications and Middleware: All software installed on the OS is the customer’s responsibility to secure.

Network Controls: While the CSP provides the network infrastructure, the customer is responsible for configuring firewalls, security groups, and network access control lists.

Data and Identity: The customer retains full responsibility for data encryption, classification, and identity and access management (IAM).

Platform as a Service (PaaS)

With PaaS, the CSP takes on more of the management burden, abstracting away the underlying infrastructure and operating systems. The provider is responsible for securing the hardware, OS, and runtime environment. The customer’s responsibility shifts to focus on what they build on the platform:

Applications: The customer is responsible for writing secure application code and managing its dependencies.

Application Configurations: Securely configuring the services and applications deployed on the platform is the customer's duty.

Data and Identity: As with IaaS, the customer remains fully responsible for securing their data and managing user access and identities.

Software as a Service (SaaS)

In a SaaS model, the provider manages the vast majority of the technology stack, including the physical infrastructure, the OS, and the application software itself. This offers the greatest ease of use but can also create a false sense of security. While the provider is responsible for application-level security, the customer always retains ultimate ownership and responsibility for critical areas:

Data: The customer is responsible for the data they enter into the application, its classification, and preventing data leakage through proper configuration.

User Access and Identity Management: The customer controls who has access to the SaaS application and what their permissions are. Enforcing strong authentication (like MFA) and the principle of least privilege is a core customer duty.

Endpoint Security: The devices used to access the SaaS application must be secured by the customer.

Function as a Service (FaaS)

FaaS, also known as serverless computing, represents the furthest point on the responsibility spectrum. The CSP manages virtually the entire stack, including the servers, OS, and runtime environment, allowing the developer to focus solely on executing code in response to events. The customer’s responsibilities become highly focused but remain critical:

Function Code: The customer is responsible for writing secure, well-formed code and managing its dependencies and libraries.

Data: The customer is responsible for the security of any data processed by or passed to the function.

Access and Configuration: The customer must securely configure the function’s triggers and manage its permissions (IAM roles) to control what resources it can access.

Across this entire spectrum, a foundational principle emerges. Regardless of the service model, there is an inescapable trinity of customer responsibility: Data, Identities, and Access Management. While the operational burden for infrastructure and platforms may shift, the ultimate guardianship of an organization’s information and the control over who can access it are non-delegable. This understanding is paramount for risk management, as it directs an organization’s finite security resources toward the areas of highest, permanent, and inalienable responsibility.

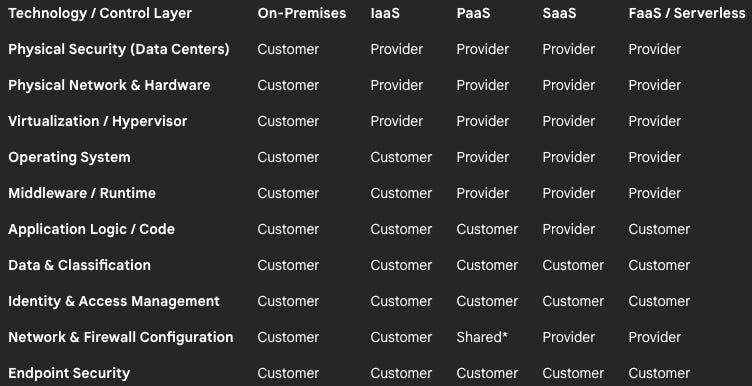

The following table provides a visual summary of how these responsibilities are delineated across the different service models, offering a clear at-a-glance reference for strategic planning.

In a PaaS model, the provider secures the platform’s network, but the customer is often responsible for configuring network access rules for their specific application deployments.

Section 2: The Extended Ecosystem: Integrating MSPs and MSSPs into the Model

For a significant number of organizations, particularly small and medium-sized businesses (SMBs), the Shared Responsibility Model is not a simple two-party relationship between them and a CSP. Instead, it is a complex, three-party system involving the customer, a Managed Service Provider (MSP) or Managed Security Service Provider (MSSP), and the underlying CSP. The MSP acts as an intermediary, taking on many of the customer’s designated responsibilities, which fundamentally alters the risk landscape and demands a more sophisticated approach to governance.

From Two Parties to Three: The New Triangle of Trust and Responsibility

When a customer engages an MSP, they effectively delegate the execution of their “security in the cloud” duties. The MSP becomes responsible for tasks such as configuring cloud services, patching guest operating systems in IaaS, monitoring for security events, and managing backups. This introduces a third party with highly privileged access to the customer’s cloud environment, transforming the linear responsibility model into a triangle of dependencies. The security and operational integrity of the MSP are now intrinsically linked to the security posture of the customer.

This relationship creates a “responsibility shadow.” The MSP’s internal security practices, their methods of system administration, their employee training programs, and their privileged access management model all become part of the customer’s extended attack surface and compliance scope. Therefore, vendor risk management for an MSP must be far more rigorous than for a typical vendor. The customer must assess the MSP as if it were an extension of their own internal security team, scrutinizing not just the services delivered but the security of the provider itself.

The Unbreakable Rule: You Can Outsource Tasks, But Not Accountability

The most critical principle in this three-party model is that while a customer can outsource the performance of security tasks, they cannot outsource the ultimate accountability for risk management and compliance. If a data breach occurs due to an MSP’s negligence, regulatory bodies and legal frameworks will hold the customer—the data owner—primarily responsible. The customer retains the non-delegable duty of due diligence, which means they are accountable for ensuring their chosen MSP is performing the required tasks correctly, securely, and in a compliant manner. Ceding more responsibility to an MSP may increase cost-efficiency, but it can also significantly increase risk exposure if not managed properly.

The Critical Role of Contracts, SLAs, and Right-to-Audit Clauses

Since accountability remains with the customer, it must be managed through robust contractual and legal instruments. The Service Level Agreement (SLA) and master service agreement become the primary tools for formally defining the MSP’s specific duties and the customer’s expectations. These legally binding documents are no longer just about uptime and performance; they are critical security and compliance artifacts.

Contracts must explicitly detail:

Which specific security controls does the MSP have responsibility for implementing and maintaining?

The MSP’s obligations for incident response include notification timelines and cooperation with the customer’s investigation team.

How the MSP will provide evidence of their security posture and control implementation.

The customer’s right to audit the MSP’s practices to gain assurance that contractual obligations are being met.

In recent years, the rise of cyber insurance and stringent regulations has transformed the SRM from a technical guide into a legal and financial liability instrument. The outdated sales pitch of “one throat to choke” is no longer viable because it is legally and financially untenable in the face of a major incident. In response, mature MSPs and MSSPs are moving away from vague marketing promises and toward formal, documented SRMs that precisely define the scope and limits of their responsibility. In a post-breach lawsuit or insurance claim, this document will be a central piece of evidence in determining negligence and assigning liability. This shift demands that businesses engage their legal, procurement, and risk management teams in the review and negotiation of these agreements with the utmost rigor.

Section 3: The Cornerstone of Clarity: Building and Operationalizing a Shared Responsibility Matrix (SRM)

The conceptual Shared Responsibility Model provides the “why,” but a formal, documented Shared Responsibility Matrix (SRM) provides the “who,” “what,” and “how.” This document, also known as a Customer Responsibility Matrix (CRM) or a RACI (Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, Informed) chart, is the non-negotiable artifact that translates the abstract model into an actionable, auditable, and enforceable plan. For organizations subject to compliance frameworks like the Cybersecurity Maturity Model Certification (CMMC), maintaining a detailed SRM is a mandatory requirement for assessment.

The process of creating an SRM is itself a valuable governance exercise. It forces critical, cross-functional conversations about risk, capability, budget, and accountability that extend far beyond the IT department. It requires input from legal teams to align with contracts, compliance teams to map to regulatory requirements, and business unit leaders to understand the impact on operations. This process elevates the SRM from a simple technical checklist to a strategic governance artifact that makes abstract cyber risk tangible, visible, and assignable.

A Practical Guide to Creating Your SRM

Developing a robust SRM involves a systematic, multi-step process that ensures clarity, completeness, and agreement among all parties.

Step 1: Identify All External Service Providers

Begin by creating a comprehensive inventory of all third-party providers that handle sensitive data or perform security-critical functions. This list must include not only the primary Cloud Service Providers (e.g., AWS, Azure, GCP) but also any MSPs, MSSPs, and critical SaaS vendors (e.g., Salesforce, Microsoft 365) that are part of the technology ecosystem.

Step 2: Select a Relevant Control Framework

Choose a comprehensive and recognized security control framework that aligns with your organization’s industry and compliance obligations. This framework will provide a structured list of controls that need to be mapped. Common choices include:

NIST SP 800-171 (the basis for CMMC Level 2)

The CIS Controls

ISO 27001 Annex A

The Cloud Security Alliance (CSA) Cloud Controls Matrix (CCM)

Step 3: Map Each Control Using a RACI Model

For every single control in the chosen framework, assign ownership and define roles. While a simple “Customer,” “Provider,” or “Shared” designation is a start, using a RACI matrix provides much-needed granularity and clarity. The roles are defined as:

Responsible (R): The person or team who does the work to implement the control.

Accountable (A): The single individual who has ultimate ownership for the correct and thorough completion of the control. There should only be one ‘A’ per control.

Consulted (C): Subject matter experts whose input is required before work is done or a decision is made.

Informed (I): People who are kept up-to-date on progress or completion.

This model eliminates ambiguity, especially in “shared” control scenarios, by specifying exactly who executes the task versus who owns the outcome.

Step 4: Document Implementation Details and Evidence Requirements

A truly effective SRM goes beyond simple role assignment. For each control, the matrix must document how the control is implemented and what specific evidence or artifacts are required to prove its effectiveness. This is crucial for internal governance and external audits. For example, for a control related to access reviews, the “Implementation Details” might specify “Quarterly review of privileged user access conducted by the IT Operations team,” and the “Evidence” would be “Signed-off access review reports stored in the compliance repository.”

Step 5: Secure Formal Sign-Off and Integrate with Contracts

The completed SRM is a foundational agreement and must be formally reviewed, understood, and signed off by all relevant parties, including the customer’s internal leadership and the external service providers. The matrix should be referenced in and aligned with the terms of SLAs and master service agreements to ensure it is contractually enforceable. It should be treated as a living document, subject to review and updates at least annually or whenever a significant change occurs in the environment or provider relationship.

The following table provides an adaptable template that organizations can use as a starting point for building their own comprehensive Shared Responsibility Matrix.

Section 4: Integrating the SRM with Governance and Risk Frameworks

The Shared Responsibility Matrix is not an isolated document; it is a critical tool for operationalizing and demonstrating compliance with major cybersecurity and risk management frameworks. These frameworks provide the “what”—the desired security outcomes and controls—while the SRM provides the “who” and “how” in a distributed, multi-vendor cloud environment. It is the essential bridge between an abstract control objective and the auditable proof of its implementation. Without a clear SRM, proving compliance in a cloud or outsourced model is a nearly impossible task for auditors and regulators.

NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) 2.0

The NIST CSF provides a high-level, risk-based approach to cybersecurity management. The SRM is the primary evidentiary document that demonstrates how an organization is implementing the CSF’s functions in a cloud context.

Govern: The new Govern function in CSF 2.0 places a strong emphasis on understanding and managing cybersecurity supply chain risks (GV.SC). The SRM is the tangible output of this process, documenting the roles, responsibilities, and accountability for every third-party provider in the supply chain.

Identify: The SRM helps define the scope of assets (ID.AM) and data flows (ID.BE) by clarifying which systems are managed internally versus by a provider. This is fundamental to any risk assessment (ID.RA).

Protect: This function includes controls for identity management, authentication, and access control (PR.AA) and data security (PR.DS). The SRM explicitly assigns ownership for implementing these safeguards, such as who is responsible for MFA enforcement versus who provides the underlying IAM platform.

Detect: The SRM clarifies who is responsible for monitoring systems for anomalies and events (DE.CM). For example, an MSSP may be responsible for monitoring network logs provided by a CSP, while the customer is responsible for monitoring application-level logs.

Respond & Recover: The SRM, when coupled with an incident response plan, delineates the roles and communication pathways for a coordinated response (RS.RP) and recovery (RC.RP) effort between the customer and its providers.

The following table illustrates how the creation and maintenance of an SRM provides direct, tangible evidence for each of the six core functions of the NIST CSF 2.0.

ISO/IEC 27001

For organizations pursuing or maintaining ISO 27001 certification, the SRM is an indispensable tool for managing the Information Security Management System (ISMS).

Statement of Applicability (SoA): The SoA is a core document in ISO 27001 that lists all controls from Annex A and justifies their inclusion or exclusion. The SRM provides the necessary detail to accurately complete the SoA by defining which controls are implemented directly by the organization, which are handled by a third-party provider, and which are shared.

Supplier Relationships (A.5): Annex A.5 (formerly A.15) requires organizations to manage information security risks associated with supplier relationships. The SRM is the primary document for defining and agreeing upon these security responsibilities with suppliers, as required by control A.5.20 (Information security in supplier agreements).

CMMC 2.0

Within the U.S. Defense Industrial Base (DIB), the SRM is not merely a best practice; it is a mandatory artifact for any organization undergoing a CMMC assessment that utilizes external service providers. CMMC is designed to ensure that contractors can adequately protect Controlled Unclassified Information (CUI). When CSPs or MSSPs are involved in handling CUI, an assessor will use the SRM as the primary roadmap to:

Verify Complete Control Coverage: The assessor will scrutinize the SRM to ensure that all 110 controls from NIST SP 800-171 (required for CMMC Level 2) are accounted for and explicitly assigned to a responsible party—the contractor, the provider, or both.

Understand the Security Boundary: The SRM defines the scope of the assessment and clarifies where the contractor’s responsibilities end and the provider’s begin.

Assess Due Diligence: A well-documented SRM demonstrates to the assessor that the organization has performed its due diligence in managing its supply chain and understands its own security obligations.

Section 5: Applying the Model to Critical Business and Support Processes

The Shared Responsibility Model extends far beyond technical security controls; it is equally critical for defining ownership and coordinating actions across essential business and support processes. Misalignment in these areas can lead to chaotic and ineffective responses during a crisis, even if technical controls are well-implemented.

Incident Response (IR)

In a cloud environment, incident response is inherently a collaborative effort, making a clear division of responsibilities essential.

Provider’s Responsibility: The CSP is responsible for detecting and responding to security incidents that affect their core cloud infrastructure, such as a physical breach of a data center or a vulnerability in their hypervisor. Their duty includes notifying affected customers in a timely manner.

Customer’s Responsibility: The customer is responsible for detecting and responding to incidents that occur within their own cloud environment. This includes events like compromised user credentials, malware on a virtual machine, an application vulnerability, or a data leakage incident caused by a misconfiguration. The customer is also responsible for all communication with their own end-users, business partners, and regulatory bodies.

Shared Responsibility: Effective incident response requires a bi-directional dependency. The customer cannot fully investigate an incident without access to logs and telemetry data provided by the CSP (e.g., network flow logs, API call logs). Conversely, the CSP may be unaware of a compromise within a customer’s tenant unless the customer detects and reports it. Therefore, the SRM and the accompanying incident response plan must pre-define contractual obligations for timely information sharing, establish clear communication channels, and outline roles for a joint investigation when necessary.

Business Continuity & Disaster Recovery (BC/DR)

One of the most common and dangerous misconceptions in cloud adoption is confusing a CSP’s infrastructure resiliency with a comprehensive customer-owned BC/DR plan.

Provider’s Responsibility: The CSP is responsible for the “resiliency of the cloud”. They provide a highly available infrastructure, often spanning multiple physical locations (Availability Zones), and offer Service Level Agreements (SLAs) for service uptime. Their sophisticated internal DR processes are designed to protect their services against unplanned downtime.

Customer’s Responsibility: The customer is solely and entirely responsible for their own BC/DR planning and “resiliency in the cloud”. A CSP’s regional outage is not the customer’s DR plan; it is the disaster event that the customer’s plan must be prepared to handle. This responsibility includes:

Data Backup: The customer is always responsible for backing up their own data.

Resilient Architecture: The customer must design their applications to be resilient, for example, by deploying them across multiple Availability Zones or regions.

Recovery Planning: The customer must define their own Recovery Time Objectives (RTO) and Recovery Point Objectives (RPO) and develop a plan to meet them.

Testing: The customer is responsible for regularly testing their disaster recovery plan to ensure it is effective.

CSP resiliency is a powerful feature that enables a customer’s DR strategy, but it is not a substitute for it.

Change Management & Configuration Control

Managing change in a dynamic cloud environment is a critical function where clear demarcation is vital to prevent security gaps.

Provider’s Responsibility: The CSP is responsible for managing changes to its underlying infrastructure, platforms, and services. A key part of this responsibility is providing clear and timely communication to customers about any changes that could potentially impact their workloads, such as API updates or service deprecations.

Customer’s Responsibility: The customer is responsible for managing all changes and configurations within their control. This includes changes to their virtual machines, applications, network firewall rules, and IAM policies. Unmanaged changes and configuration drift are among the leading causes of cloud data breaches and security incidents.

Shared Responsibility: This is a classic shared control area. The CSP provides the configurable services, but the customer is ultimately responsible for how those services are securely configured. Many CSPs offer tools to help customers monitor for problematic configurations, but the responsibility to remediate them remains with the customer.

Section 6: Common Pitfalls and Strategic Recommendations

Despite the conceptual clarity of the Shared Responsibility Model, its practical implementation is fraught with challenges. The root cause of most SRM failures is not a lack of sophisticated security technology, but rather a breakdown in fundamental organizational processes: a lack of understanding, incorrect assumptions, poor communication, and a failure to establish clear ownership. These human and organizational factors lead to predictable and preventable security gaps.

Identifying the Gaps

Several common pitfalls consistently emerge as the primary causes of security incidents in the cloud:

Misunderstanding and Over-delegation: The most pervasive failure is a fundamental misunderstanding of the model itself. A significant percentage of IT and cybersecurity professionals are not fully familiar with the SRM, leading them to assume the cloud provider handles far more security than they actually do. This “over-delegation” results in a complete failure to address customer-side responsibilities, leaving critical security domains like data protection and access control unmanaged.

Reliance on Default Settings: Many cloud services are configured with default settings that prioritize ease of use and functionality over maximum security. A common mistake is for customers to deploy services using these defaults without hardening them according to security best practices. For example, failing to enable multi-factor authentication (MFA) or leaving storage buckets publicly accessible are frequent errors that stem from accepting insecure defaults.

Lack of Visibility and Accountability: Without a formal SRM document and continuous monitoring, organizations operate with significant blind spots. They may lack insight into their cloud environment, have insufficient oversight of their providers’ actions, and possess no documented evidence to prove compliance or performance. When responsibility is ambiguous, accountability becomes impossible.

Expert Recommendations

To close these gaps and build a mature cloud security program, organizations must adopt a strategic and disciplined approach to operationalizing the Shared Responsibility Model.

Treat the SRM as a Living, Legally-Binding Document: The Shared Responsibility Matrix should not be a one-time, check-the-box exercise. It must be treated as a living document that is formally reviewed at least annually and anytime a new service is adopted, a new provider is engaged, or a significant architectural change is made. Crucially, the responsibilities outlined in the SRM must be explicitly referenced and incorporated into master service agreements (MSAs) and SLAs to ensure they are legally and contractually enforceable.

Implement Continuous Monitoring and Automation: Manually auditing complex cloud environments is not scalable or effective. Organizations must leverage technology to enforce their side of the responsibility model. Tools like Cloud Security Posture Management (CSPM) can continuously scan cloud environments for misconfigurations, policy violations, and security risks, providing automated alerts and, in some cases, remediation. This allows security teams to manage customer-controlled configurations at scale.

Conduct Rigorous Vendor Risk Assessments: Before onboarding any new provider—whether a CSP, MSP, or SaaS vendor—organizations must conduct thorough due diligence. This process should go beyond a simple questionnaire. It must involve a detailed review of the provider’s own SRM documentation, their compliance attestations (e.g., SOC 2, ISO 27001), and a meticulous examination of their SLAs to identify any gaps or ambiguities in their stated responsibilities.

Invest in Continuous and Role-Based Training: Human error is the leading cause of cloud misconfigurations. Therefore, continuous training is one of the most effective security controls. All teams involved in the cloud ecosystem—from developers and cloud architects to security operations and IT staff—must be trained on their specific responsibilities within the model. This ensures that everyone understands their role in protecting the organization’s assets in the cloud.

Conclusion: From Shared Responsibility to Strategic Advantage

The Shared Responsibility Model is far more than a technical diagram in a cloud provider’s documentation; it is the central organizing principle for security, risk, and governance in the modern IT landscape. As this report has demonstrated, a superficial understanding of the model is insufficient and dangerous. True cyber resilience requires a deep, multi-layered comprehension that extends beyond the primary Cloud Service Provider to encompass the entire ecosystem of Managed Service Providers, security vendors, and SaaS applications that power the contemporary enterprise.

The journey to mastering this model begins with deconstructing its foundational tenets—understanding the shifting lines of responsibility across IaaS, PaaS, SaaS, and FaaS, while recognizing the inescapable customer ownership of data, identities, and access. It then requires expanding this view to the complex three-party reality introduced by MSPs and MSSPs, where tasks can be delegated but ultimate accountability cannot. The cornerstone of this mastery is the creation and operationalization of a formal Shared Responsibility Matrix. This document transforms abstract principles into an actionable, auditable, and legally enforceable plan, serving as the critical link between security operations and governance frameworks like NIST CSF, ISO 27001, and CMMC.

By applying this disciplined approach to critical business processes such as incident response and disaster recovery, and by vigilantly avoiding common pitfalls like over-delegation and reliance on insecure defaults, an organization can transform the Shared Responsibility Model from a source of confusion and risk into a source of strategic advantage. Achieving this level of clarity eliminates security gaps, streamlines compliance efforts, enables the negotiation of stronger contracts, and fosters a culture of accountability. Ultimately, mastering the Shared Responsibility Model is a hallmark of a mature cloud organization, empowering it to leverage the full power and agility of the cloud with confidence, control, and resilience.

Why not give the gift of a subscription to the SMB Tech & Cybersecurity Leadership newsletter to your team members or mentees in the community who you have been helping? Here is your opportunity!